Prerana

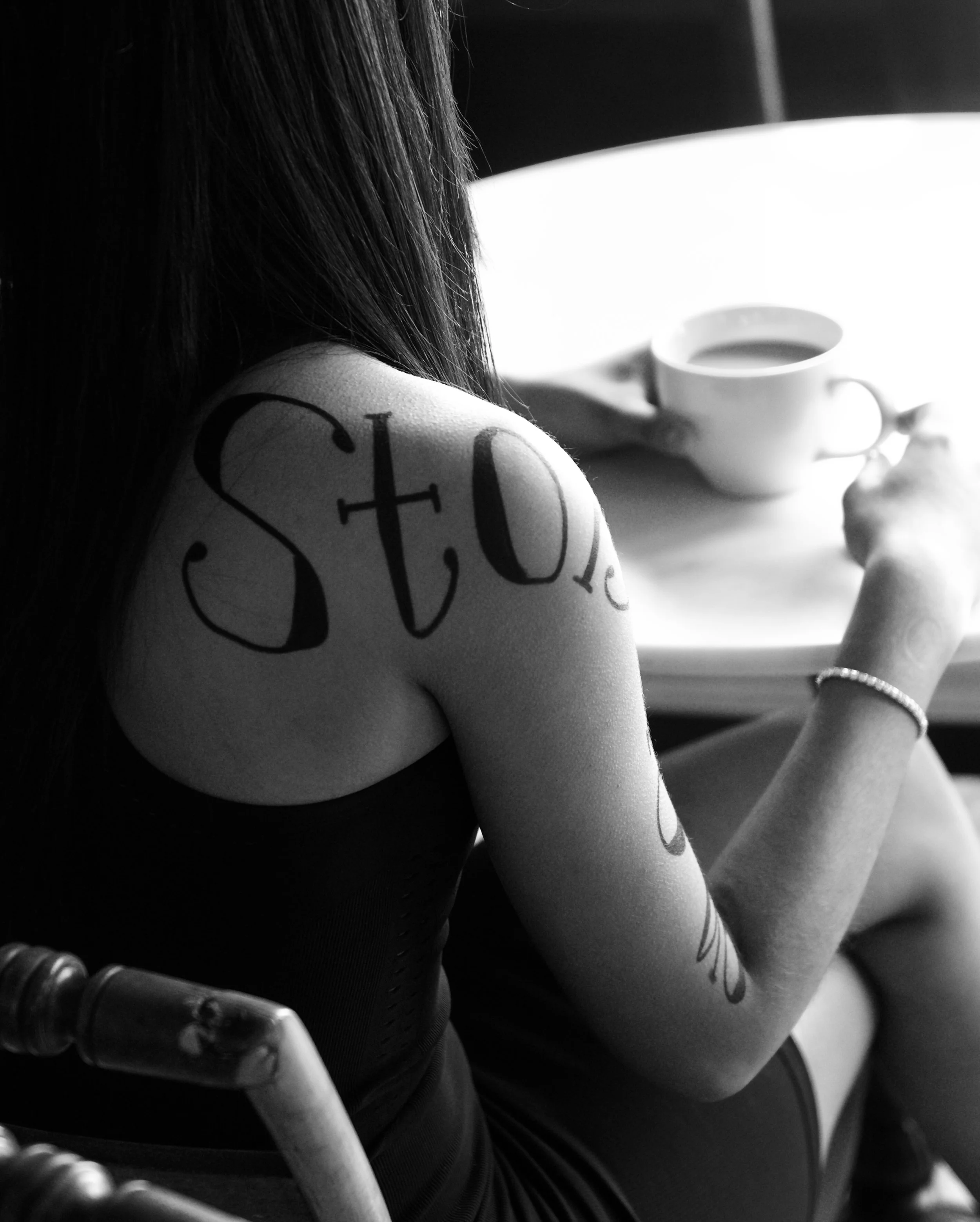

“Every story is us.”

-RumiI was never the person who always wanted to become a doctor.To tell my story, I first have to highlight that I am the daughter of immigrants. My parents moved to America from India when I was six months old, so this is the only place I ever remember growing up. My parents knew how to speak English, so they didn’t have a language barrier when they moved, but there was so much they had to learn – things as simple as going to the grocery store and navigating a whole new school system with two young daughters. They started from square one in a tiny one bedroom apartment and worked their way up for my sister and I to have more opportunities. Knowing where they started and where they ended up has always guided me.My mom and my grandma always wanted to be doctors. I remember hearing stories about how my grandma would sneak Anatomy and Physiology textbooks from her grandfather’s library and read them for fun. Because of the societal norms for women in India and the construct of our family at the time, becoming a doctor was just not an option for her. And then my mom’s turn came around. She was brilliant, number one in her class, and she easily could have been accepted to medical school – but again, due to a combination of financial and societal expectations, it was not possible for her either.On the day of my White Coat Ceremony in medical school, an event that marks the start of training for future physicians, my mom gave me a letter from my grandma. My grandma had died from Hodgkin’s lymphoma five years earlier, and my mom and aunt had uncovered a diary in which she had written letters to her grandchildren. My grandma knew I was considering medicine, but she passed away before I applied and was accepted to medical school. I sobbed when I read her letter. The lines that stick out the most to me are, “Times have changed and you are in a better place for a girl. You are lucky to be in a place where you can become anything. ”I never take that for granted.I was never pressured to go into medicine. A few of my family members have PhDs, and I knew I liked biology, so I thought I was going to go into research. But when I started working in a lab in college, I realized that I am a person who is really driven and motivated by human connection; that is my joy. Medicine was a way for me to use scientific knowledge to actually connect with people and make their lives better. I started shadowing doctors and volunteering in hospitals, and I realized that this was the right path for me. Being pre-med is stressful. When I was accepted to Cornell, it felt like the best thing that could have happened to me at the time. Ivy League school; I had made it. But college was hard for me in ways I didn’t expect. Everyone around me was stressed all the time, and it constantly felt like a pressure cooker. Applying to medical school is a very competitive process. The classes are curved, so your success depends on doing better than the people around you. That concept was really hard and unnatural for me.That pressure to be perfect continued into medical school. There was a sense that you always had to be “on.” I don’t think I ever truly doubted my decision to go into medicine, but I did often doubt my ability to do it. No one in my family is a doctor, and I am a woman of color. I had internalized subtle messaging I had received that I did not belong in the medical field. I had a voice in my head saying “You’re behind. Everyone else has this basic understanding of medicine you don’t have. You’re behind.” Imposter syndrome is challenging to have, especially in a system where you start out with very little clinical experience and are learning so much every day. That insecurity has quieted a bit with time, but it’s still something that can crop up. I could not have gone through this process alone and am thankful to have had incredible mentors and friends who supported me along the way. I have built such long-lasting relationships and memories with the people who guided me through. I would not be where I am today without them. I am equally thankful for the patients I learned from in medical school - they were my greatest teachers.One challenging aspect of the medical education process is that you are constantly faced with the concept of delayed gratification. In every step of your schooling, there is this idea that you need to get through your current stage to make it to the next thing, with the promise that one day you’ll be where you want to be. I think when you’re conditioned to endlessly think about your future trajectory, it takes you away from being fully present in moments of human connection.I learned over time that I needed to be more intentional about grounding myself and reminding myself, “Even in training, these patient interactions ARE important. This is actually why I went into medicine. It wasn’t to check off these boxes I’m being told I need to check off.”One of the quotes I almost chose for this project is by Paul Kalanithi from his book “When Breath Becomes Air.” He was a doctor who was diagnosed with cancer during his medical training, and he wrote his reflections before he ultimately passed. The quote is: “There is a moment, a cusp, when the sum of gathered experience is worn down by the details of daily living. We are never so wise as when we live in this moment.”I remember reading that in medical school and thinking, “Ohhh, I need to reframe this for myself. I’m so focused on where I’m going to match and what specialty I might go into that I’m losing sight of the fact that I’m having these really formative experiences.” I think this is an important reflection for life in general.When all you can think is, “What’s the next thing?,” it can be hard to simply ground yourself where you actually are.I was so excited when I got to my fourth year of medical school – it was the year I had been waiting for. It's the year that medical students are able to finally relax a little bit and maybe even take a vacation. Instead, we were hit with a global pandemic. The world shut down one week before my classmates and I matched for residency. We held Match Day (a ceremony where fourth year medical students find out which hospital they are going to for residency, their next step of training) and graduation virtually.I have this video from my graduation ceremony, where my parents put my hood on, and I officially became a doctor. And I’m sobbing. I’m sobbing in my living room. I think my parents thought I was emotional because I was becoming a doctor, but it was actually a mix of emotions: it was really hard to be isolated from my medical school friends and mentors, but also, I had a lot of fear.I watched as my mentors bravely took care of patients on the frontlines. It was very scary to enter the healthcare profession at that time. I was going into pediatrics, and we didn’t know how the pandemic was ultimately going to impact children. We didn’t know how it was going to impact our training. We wondered if we were going to be needed to help adult ICUs. There was no choice but to power through and think, “This is just what we’re doing. This is what’s happening.”On top of that, I was moving to a new city, and right before I moved, my family and I got into a horrible car accident. Our car flipped over. Windows shattered, and we had to crawl through a window to get out. It was so scary. All of these things were happening for me at the same time. Pandemic. Becoming a healthcare worker. Moving to a new city. Car accident. And then it was like “All right! Time to start residency. Time to be a doctor.”It was a lot. I powered through it, and I didn’t really sit with how scary it was. I almost felt like I couldn’t, because if I thought about it too much, I wouldn’t have been able to keep going.At the end of my first year of residency, I remember writing, “Starting residency is having the highlight reel of humanity brought into view in a single moment. Starting residency in a pandemic is having that highlight reel constantly refocused and reconfigured.” That’s exactly what it was. At baseline, residency is crazy. You’ve transitioned from being a relatively sheltered medical student to feeling the weight of increased responsibility for your patients.Nothing really prepares you for seeing the hardest and worst things happen to children every day. What was unique about my class’s residency experience was that the pandemic really altered the landscape of pediatric illness. During my first year, we saw so many patients with mental health struggles. It makes sense, right? Children are not meant to be isolated. They’re not meant to be taken out of school and away from their friends. And we definitely saw the impact of that. On top of some typical pediatric ailments, we saw a lot of patients with eating disorders and suicidal ideation.The physical isolation that we experienced that year was also tough. I was going to work, I was coming home, and I was not doing much in between. I was seeing all of these really hard things happen to children, but didn’t have my normal coping mechanisms. I was trying not to go home and see my parents because of the risk of COVID exposure. Over time, when going to work and coming home is what you are doing all day and your outlets are taken away, it’s easy to believe that that’s all the world is. I would not have made it through without my coresidents, who have become some of my best friends. But it was tough for all of us.Interestingly, in spite of all this, during my first year of residency, things were not as hard for me with my personal mental health. I was deeply in a mindset of “I need to power through.” In pediatrics, patient numbers were actually lower that year, because children were not as affected by the first wave of COVID. I also was so happy just to have human connection again - to see my coresidents and take care of patients. I was making the best of a crazy situation.But you can only power through something for so long before it catches up with you, and things really came to a head for me during my second year of residency. By the winter of that year, my mental health took a hit. It was during that time that I was doing a lot of my harder rotations, like the pediatric ICU and Oncology. There was a week where one of my patients died almost every day. Also around that time, the pediatric volumes really started to go up to unprecedented numbers. COVID mutated to Omicron, and kids were back in school. With all of that, kids got sick so fast, and in record numbers. Our ED waiting room was spilling over.We were just running around like crazy. There were so many sick children with respiratory illnesses, many on ventilators…I don’t know that people generally were clued in to how challenging it was to be a pediatrician at that time. In the early days of the pandemic, the message was, “Doctors are healthcare heroes!”. But in pediatrics, I felt a lot of dissonance with that, because pediatric volumes were lower at that point. And then when our volumes spiked a year later, public opinion seemed to change about doctors. It was tough.Looking back on that year, it’s hard for me to think about how low it got, but it got low. There was a period of time where I was crying a lot. It was hard to wake up and go to work. Thankfully, it did not last long, but it was challenging. I was just mentally, emotionally, and physically exhausted. And that is so different from who I am normally.I think it’s also important to point out how sheer physical exhaustion can contribute to these feelings. In residency, you commonly work 24 hours at a stretch. You’re working 80 hours per week. There are times you’re working nights for over two weeks. I laugh about it now, but once I literally got lost walking home from a long call because I was so tired that I zoned out and walked around in circles. I was like, “Oh my God, I just need to get home.” We’re talking crazy levels of exhaustion. That physical exhaustion layered on top of mental exhaustion was a lot. No wonder I got to second year and was tired. Of course I was.One of my core values is gratitude. And I feel that for the medical profession. I feel so lucky that I get to take care of children every day. I feel lucky to have the opportunity to make a difference. But I learned something when talking to one of my mentors during my second year of residency. She said to me, “Maybe you’re just not grateful right now. And that’s ok.” She told me, “Maybe you just need to sit with the fact that in this moment, you can’t be grateful – because you’re just tired.” And I think what I learned from that is that it’s okay to hold that gratitude in one hand and also hold exhaustion and sadness or even frustration and grief in the other. I had to take a step back and tell myself, “Maybe just for a minute, you need to feel sad. Maybe it’s time to just be upset, and then you’ll bounce back from it. But you need to feel it first.”I worry a lot about the wellbeing of medical professionals. In particular, I worry about trainees who are particularly vulnerable, not only because of their physical and mental exhaustion, but also because of power dynamics. Just last month, a resident at another hospital died by suicide. It’s my understanding that he largely cited the issues with medical training and how hard the system is. I do think it’s getting more acceptable to openly say, “I’m struggling” or to seek therapy, and I think there are more tangible avenues in place for people who are struggling, but for a long time the conversation has been about teaching healthcare workers to be resilient.In my opinion, you’re looking at people who went through the medical training system and see traumatic events every day – they ARE resilient. Maybe it is actually the external factors that need to be looked at and not the individual people. But I do see the conversation changing in positive ways in so many institutions, and I think that’s really important.The realities of this job can make it hard to always show up in the ways we want to. You’re constantly juggling competing interests. One story that highlights this is when I was working in the emergency room and we resuscitated an infant who had undergone cardiac arrest. The baby ended up passing away. And ten minutes later, I had to perform a lumbar puncture on another patient. When I went into the room, the parents understandably were like, “Where have you been? I thought you were going to do this an hour ago.” Their reaction made sense of course; they had no idea what else had been going on. And I just had to apologize. There was no time to process.The amount of time we spend at the bedside is also just such a small piece of what we’re actually doing every day. It’s a constant balancing act. I’m often thinking, “Okay, I have to see this patient, then I have to message consultants, then I have to write my note, then I have to make this call and do this admission…” It’s increasingly harder to just be present with patients, because you’re constantly pulled away from the bedside. And yet, our job is to be the person who walks into the room of a child and tells the parents, “We’re worried your child may have cancer.” Or to reveal that their child has diabetes, knowing their life is going to change in a second based on what we say. For families, this is their moment. This is their hard moment, and they deserve someone who is going to walk alongside them with thoughtfulness, compassion, and empathy. That is what they deserve. So amidst the exhaustion and the task list, you do your best to give that to them. And you have multiple interactions like this every day. This is what we signed up for, and it is an immense privilege, but it can be hard to balance.Something that has grounded me is narrative medicine. I have always loved to write – I minored in English at Cornell. During college, I wrote a portfolio of poetry inspired by my early patient experiences. I shifted more to reflective writing in medical school. It has always been instrumental in helping me fight that mentality of constantly moving onto the next thing. It pushes me to stop and reflect deeply on my patient interactions. I’m always touched when people read what I’ve written and say, “I felt that!”But I essentially stopped writing during residency. I think part of that was because of confidentiality issues, which is always important in our profession. But honestly, during residency, I felt like I didn’t even want to stop and think about things. It was too overwhelming. I was living it every day, and I needed to put it in a box and step away from it. It’s only now, being out of residency for a few months, that I have been able to sit down and unpack it.The process of unpacking has been really healing. Now that I’m a hospitalist, I’m still taking care of patients, but I have much more space and time to sit with everything and take care of myself. Basic necessities, like cleaning my apartment and doing my laundry, are actually happening. I go to Soul Cycle a few times per week, so I get to be in a dark room with good music and sweat and heal that way. I go for walks, I read, I sit with my morning cup of coffee. Having space to take care of myself makes it so much easier to take care of others.Another quote I almost used for this project is by Yung Pueblo: “I can only give to you what I have already given to myself.” I think that this is a lesson I learned towards the end of residency. I had to acknowledge that what I was doing was not sustainable. I had to take care of myself. I am starting fellowship (subspecialty training) in a few months, and I now feel recovered and ready.I do think that when appropriate, it is important for us to share our perspective as doctors. We witness so much of the human experience every single day. I am often face-to-face with the outcomes of social determinants of health. I see the impact of poverty daily. I see what it means for patients who don’t have access to safe housing. So many elements are interconnected. For instance, when kids don’t have safe places to play outside because of violence, they’re inside a lot, which impacts obesity and diabetes rates. If they live in a community where there is mold in the home, this can also worsen asthma. It troubles me so much when the conversation centers around “parents need to try harder.” They are prioritizing keeping their children safe, and it feels like we are failing them. I regularly see the impact of gun violence. I have taken care of young patients with gunshot wounds. I have had children in the clinic tell me that they were recently at a friend’s funeral because their friend had been shot. It’s hard to then turn on the news and hear people say, “It’s not the guns.” I frequently find myself thinking, “I wish you could see what I see.”“I wish you could see what I see.” I think about it all the time. Sometimes, when I come face-to-face with the medical misinformation that’s out there, it’s scary. I’ve seen devastating outcomes of people taking medical advice from unreliable sources rather than having a conversation with their doctor. I had a patient with a toxic ingestion because his family member gave him something he should have not ingested, and he ended up with so much damage to his esophagus he couldn’t eat anymore. I took care of a patient who developed a serious, progressive brain injury as a complication of measles. The patient was too young to be vaccinated, but they were around others who were unvaccinated and subsequently contracted measles. As a result, they developed this fatal and irreversible neurological illness. When I see these things, all I can think is, “We have got to turn this around. This has genuine consequences.”I can recognize where some of this mistrust in the medical system comes from. Historically, the medical system has done so much wrong by patients - Black patients and patients of underrepresented minorities in particular. It is very valid for patients to have a deep-seated mistrust of that system. In generations past, medicine has largely been a white, male profession. It is really hard for patients to look at doctors and not see anyone who looks like them, and think, “Okay, I’m just going to inherently trust you with all of these things,” especially when they have very valid reasons for that lack of trust. I think there’s a lot of healing that needs to happen. And, of course, no doctor is perfect; there will be times we don’t show up in the right way. We don’t always do it right. That said, I do think things are improving. We have a long way to go, but there is increasingly more diversity in the medical field. It is important we continue to highlight efforts to enhance diversity, equity and inclusion in our profession, especially efforts to elevate Black doctors and doctors of underrepresented minorities. I think medical training is changing too. We are taught much more now about bedside manner and what it means to be a compassionate provider. Medicine used to be more prescriptive, but there’s been progress in our training towards medicine as a partnership.The misconceptions about medicine used to frustrate me, but since I’ve had more experience, when I sit down with parents now, I think I do a better job of meeting people where they are while trying to at least share my perspective. For example, I know many parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children. But they don’t have the experience of seeing a child die from measles. So I take the approach of - let’s see if we can find some common ground here. Building trust and mutual respect is the most important thing. It’s crucial to have that before tackling challenging medical conversations. Getting on the same page can be hard sometimes. As doctors, we are bringing our own perspectives to our patient interactions. We have to be thoughtful about checking that and reminding ourselves, “Okay, I may feel strongly about this, but what will actually work for this patient and family?”When I’m with my patients, I don’t view myself as being the person “in charge.” I think humanizing moments are really important, even if they’re small. It’s important to consciously think, “We’re both human beings, let’s lower the power dynamic and work together.” It’s a silly example, but this is the City of Philadelphia, and we love our sports teams (Go Birds!). We love our Eagles. So when I walk into a room and see that a parent is wearing an Eagles jersey, I’ll ask them, “What did you guys think about the game?” Even something as simple as that humanizes the interaction a bit. It can be disarming. It makes me a little more of a normal person in their eyes. It’s like, “Let me see you as a person, and let me allow you to see me as a person.” It can go a long way. To be honest, I think we all have a lot more in common than we think we do. It’s all about human connection. At the end of residency, I did a global health rotation in Botswana. They have a very different style of hospital layout - it is ward style where there is a large room with beds next to one another and each parent sits with their child. When I was there, I noticed that when one parent would go through something hard, the parents from the surrounding beds would come over to offer support. They would share food and watch each other’s children if one parent had to go home. Witnessing that gave me so much clarity. Comparing those interactions to the isolation we experienced in the pandemic showed me the impact we can have when we are able to be there for one another. There are these intrinsic aspects of the human experience that unite us, and if anything, that’s what I’ve learned over the past few years. Your twenties are a really formative time in life, and I spent the majority of mine in medical training. There are some things I missed out on, but there is so much that I gained. Going through this process has given me a good amount of perspective.I have gained a lot of humility. As much as I’ve talked about how it can be hard to be a doctor, it is so much harder to be a patient or family member. I truly cannot imagine spending a day in their shoes. As hard as this job can be, it is ten times harder to be living the experience. You also learn so much about what it means to be human. You see injustice, pain, and sorrow; and you learn that not everything is fixable. It’s not always a curable disease. You can’t always transplant a child out of a harmful environment, no matter how much you might want to. Sometimes you can’t save a child’s life. It’s hard to bear that.But there’s still so much beauty, even in the hard times. Even in the ways we are able to show up for children. A teenager once came out to me as trans and said, “You’re the first person I ever told.” Knowing they felt safe enough to say that to me…that is the beauty of this job. Another patient had a terminal illness but really wanted to make it to a sporting event. We made that happen before he passed away. That was beautiful. There is also incredible beauty in the ways parents show up for their children. It inspires me every day.I know in a deep part of myself that nothing is guaranteed, and it just makes me appreciate all of the good days. All of the moments of joy. I intentionally do things that make me happy, because you never know what can be taken away. I’m so appreciative of every single moment.When you go into medicine, you learn all about how a body works. But to me, that’s not what human knowledge is. Human knowledge is about the relationships you form with other people and the ways in which your stories intersect. Those relationships are part of a larger knowledge that deeply informs the world we live in. I have learned that through the highs and lows; we are all so connected and part of each others’ stories. And that’s why I chose this quote:“Every story is us.”